An open wound

I was born in Beirut sixty one days after the massacre of Sabra and Shatila in 1982. The first memory for me in beirut, the one I can still recall with clarity, happened when I was barely three years old. I remember that there were intense clashes outside our ground floor apartment when suddenly a bullet penetrated through the balcony glass door going through the wood cupboard of the dining room making its way to the living room and landed in between my feet. As soon as I noticed the orange glowing at my feet I reached for it. Not minding the storm of screams and shouts that was directed at me from my mother, father and grandfather, “nooooo its a bullet, don’t not touch it…” but I did and screamed in agony as soon as I picked it up. This was not the first time death lurked around our home in Beirut. My mum tells me that when I was nine months old an RPG exploded on our balcony and the whole glass sheet from the window shattered all over me while I was tucked under the duvet.

Growing up during the war I listened to family members lament that the lebanese civil war of 1975 had no beginning and no end. I never understood what they meant. Thereafter, when the war ended I started noticing how people were dumbstruck by the fact that the shooting had stopped but the horror show with the same actors resumed in Lebanon. In the nineties, following the ceasefire, economic exploitation by sectarian warlords became business du jour. With the Syrian security “keeping the peace” Lebanese warlords turned politicians applied the same civil war quotas amongst themselves to divide State assets and racketeer the public sector. Last week we witnessed a new episode of the horror show when on august 4 the port of Beirut blew up and destroyed the city. The damage caused by the explosion was similar to what took fifteen years of civil war. As if nothing changed, the pattern repeats itself once again.

Before we delve into the blast I would like to reflect on the geographic location where it took place. In the past this area has witnessed hideous crimes and slaughter. Around the port vicinity the infamous Maslakh (slaughterhouse) incident happened where Kurds and Palestinians lived; Karantina, was the location where the homes of 10,000 people were razed to the ground as right-wing Christian militias “cleansed” the city. A bit further north used to be the location of Tel al-Zaatar, a large Palestinian camp housing over 30,000 Palestinian refugees. The camp came under siege in spring of 1976. When the camp surrendered Palestinian refugees began evacuating the camp. As they came out, children, men and women, all civilians with the assistance of the international red cross, met a sort of barbarism that set the standard for the Lebanese civil war.

The Blast

The massive explosion on August 4 is another horrific crime in which more than 150 people have died and over 6000 have been injured. Over 300,000 people have been made homeless and tens are still missing. Among the dead were more than 40 Syrians, low wage port workers, volunteers and rescuers who rushed to put off the fire and low ranking soldiers. According to preliminary estimates, material losses caused by the blast exceeds five billion dollars. Beirut is now declared, once again, a disaster city.

A few hours following the blast we were told by the government that an investigation committee was formed, with a detailed report to be issued within five days. Five days have passed, we are yet to hear any results. Although the possibility of an act of sabotage behind the bombing cannot be excluded from the circle of investigation, the main assumption from the local journalists and official security accounts describe a pattern of negligence adhesive with corruption that led to the blast.

The blast was caused by 2750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate stored in a warehouse at the port. It is yet unclear what set off the explosion. We know now that there was a fire that preceded the blast which might have caused the perfect conditions for the explosion. Another noteworthy detail is the fact that people in the vicinity of the port reported hearing isreali fighter jets in the sky during the day before the explosion. This is a significant detail, one must assume that since the israelis were watching from above they must have seen (or triggered) what happened.

Videos shared on social media show the crackling of fireworks in the same storage facility, hangar number 12, prior to the blast. “100 per cent of explosions of ammonium nitrate in storage are due to uncontrolled fires,” says Vyto Babrauskas, a New York-based consultant who has written several papers on ammonium nitrate accidents.

Ammonium nitrate, a common fertiliser additive, is a white crystalline solid at room temperature. It is stable except when it is contaminated with organic (carbon-based) material. In practice, it is commonly mixed with fuel oil to form an industrial explosive (called ammonium nitrate/fuel oil, or ANFO) and is widely used in the mining industry.

Ammonium nitrate is much more explosive when mixed with carbon compounds such as fuel oil or even coal dust. According to reports by NewScientist “There have been numerous explosions around the world due to ammonium nitrate. The most recent was in Texas in 2013, when 15 people died after an explosion in a fertiliser warehouse. Video footage of that explosion resembles that from Beirut, says Babrauskas. ‘Beirut is the same thing, just done bigger.’”

During the day

The primary sources about the incident said that that day blacksmiths were commissioned to fill the gap and weld the door of the hangar 12 where the ammonium was stored. Shortly after the welding job was done fire started inside the storage and lasted for about half an hour turning into a growing blaze that ignited a cache of fireworks leading to the explosion.

For the explosion to detonate in hangar 12 something had to heat the ammonium nitrate to a critical temperature of 300C for it to auto-ignite. According to investigative journalist Riad Qobaisi there were other highly flammable materials stored in that same storage. So according to this probability there is still a gap in between the time the blacksmith left the spot and when fire started. Which leaves speculation open about what started the fire: was it sparks from the welding torch-gun that caused the fire inside creating the perfect conditions of high temperatures levels for ammonium and nitrogen dioxide to form so ammonium nitrate breaks down and reacts together to produce massive amounts of heat? Or is it an act of sabotage that took advantage of the welding repair job done at the time?

Another crucial detail is worth considering before we start to self flagellate and go on to fratricide one another. We have to keep our thinking scientific. Thus, we shouldn’t exclude the possibility that the bomb of negligence and corruption was possibly detonated from above. And that with all the technology available today the sky archives of that day should be examined ASAP.

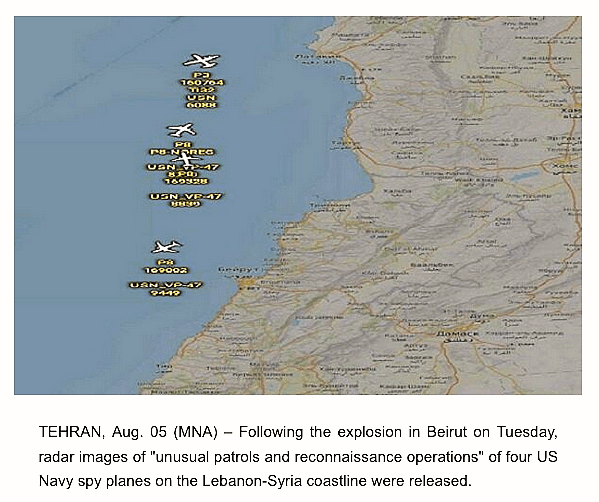

According to MEHR new agency, “radar images of unusual patrols and reconnaissance operations of four US Navy spy planes on the Lebanon-Syria coastline were released after the powerful explosion in the port of Beirut. In this regard, some security experts said that there is possibility of US sabotage, adding that US forces may have planned a sabotage operation in recent days.”

Here we must ask the Americans for an immediate release of a Freedom of Information Act to find out if US Navy spy planes were above watching. We need to know what they saw, or did. The president of the United States might have slipped when he first announced, “It looks like a terrible attack.” And then he went on saying, “They seem to think it was an attack. It was a bomb of some kind, yes.”

Where did it come from?

The 2750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate found its way to beirut when a ship bound to Mozambique in 2013 was confiscated at the port of Beirut after developing technical problems. The ship wasn’t allowed to continue its voyage because of the prohibited material it carried. Later, the ship was abandoned by the owners, and its cargo moved to hangar 12. The Moldovan ship that brought the shipment of ammonium nitrate to the Lebanese sea eventually sank after years of confiscation. Its hull today lies at the bottom of the sea of the harbor which was destroyed by the blast.

According to the captain of the ship Rhosos, in an interview with Al-Arabi, “the lebanese authorities refrained at first from unloading the ship saying that the ammonium on it was highly explosive and prohibited material not to be stored at the port. He went on saying that, “the ship was later unloaded. I learned about it when I was in custody by the lawyer that took our case.”

In June 2019, State Security, one of the highest security agencies in Lebanon, launched an investigation into the cargo, after repeated complaints of foul odors emanating from the hangar 12. The report said the warehouse contained hazardous materials that need to be moved. The report also stated that the walls of the hanger number 12 were cracked and recommended that it be repaired.

This is where the story of lethal corruption and nepotism begins.

The clock on the bomb started ticking the moment the current Director General of Customs and his predecessor decided to hold the shipload in hangar 12 instead of disposing of it through proper channels. It’s highly likely that they saw in the abandoned ammonium an opportunity and decided to sell it locally. Moreover, after emptying the ship that was abandoned by its owners the same port authorities kept the ship afloat in order to auction it. The ammonium was unloaded from the ship and placed in hangar 12 under guard. The only people who were in charge of guarding hangar 12 are the customs authorities and the executive management of the port. Significantly, the unloaded ammonium was merely stored but not legally confiscated and this technical difference could have possibly meant that it was kept until a legal loophole was made available to enable its sale.

Shortly after the explosion the Director General of Customs, Badri Daher, popped up on news channels claiming that he didn’t know what had happened and adding that he was “in the toilet.” A classic Lebanese official first response: it wasn’t me.

Two days after the blast information leaked through local media channels regarding the Director General of Customs, Badri Daher, who refused to appear before the investigators, on the pretext that, at times, he was with the President, and at other times he was busy while being involved with the Crisis Commission. Daher was arrested on Friday the 7th three days after the blast.

In an interview with Al-Akhbar newspaper Daher said, “I have done more than my duty”, considering that despite the existence of a judicial decision, he repeated his communication with the judge about the extent of the danger the materials presented, passing responsibility on to the port executive authority.

Correspondence between the ministry of transport and the customs ensued following the unloading and storage of ammonium. We are told by local journalists that year after year the same attempt was made by the customs authority of the port to get the legal leeways to enable the proceedings, presumably, for the sale of the ammonium in storage. The last attempt by the Director General of Customs to acquire a legal loophole from an unspecialised court was made on 12-07-2018.

Sales of sequestrated goods at ports is an age old habit that occurs all over the world. However, this habit in Lebanon took on a whole different level of corruption when the previous Director General of Customs at the port was able to sell a confiscated asbestos shipment under the pretext of forming a threat to the country. The same Director General was exposed for involvement in aiding and abetting the entry of counterfeit cancer medication that was sold on the market for years. After the story was made public the Director General received political cover and never faced justice.

Since 2015 the port’s customs authorities have attempted every year to plead with the interim relief court to issue the customs a release order so they can do whatever was in plan for the stored ammonium (most likely sell it). However, their requests were rejected by the interim relief judge who requested further correspondence about the details of the request which the port customs authorities refrained from supplying. In short what the customs were trying to do is put pressure on an unspecialised court, by creating an urgent request they thought they could justify by the fact that it was hazardous material and urgently needed a permit from court. Instead of having to go through the proper channels that will have the ammonium disposed through under another security apparatus outside the port vicinity. And since ammonium is a prohibited item the port authorities couldn’t just sell it at the periodic auction of abandoned goods. According to local journalist Riad Qobaisi who has been investigating the corruption at the port for years: Badri Daher was trying to find a legal cover, from an unspecialised court, to shadow the kind of illegal practice which forms a pattern of the rampant corruption that runs the show at the port of Beirut.

Law article 205 stipulates that it’s forbidden to store at the dock all kinds of gunpowder, explosive material and flammable substance or any material that might cause a threat to the facility. In february 2014 the military sent a memo to the port customs authorities recommending the immediate removal of the ship carrying ammonium from port. Later in 2015, the Army’s Equipment Directorate revealed samples of these materials, which showed that the concentration of nitrogen in them was 34.7, meaning that it was considered as highly destructive materials that must be disposed of. And from there on every year a new round of inspections and recommendations was issued warning about the material at port. We just found out that only recently, in February of this year, the current prime minister Hassan Diab was also briefed about the dangerous ammonium. Everybody knew but no one took any action. The question that begs is why were these recommendations ignored over and over again? Clearly someone saw profit in it.

How come the customs authorities, as it claimed by its chief, didn’t notice all those years that the ammonium was stored in the same storage next to confiscated boxes of fireworks that should’ve been impounded by the Lebanese military in Yarzi. Also inside the same hunger 12 was stored rubber tires, thinner and paint barrels. That’s the question that people are demanding answers to. That there at the port casually sat a bomb concoction ready for detonation. Worst of all is the realisation now that this apocalyptic disaster was completely preventable.

The picture that has shocked people in the last few days shows firefighters minutes before the blast trying to break the locks and open the storage on fire. The storage door had two locks, one key is kept with the executive management of the port and another key is held with the port’s customs authorities. Both executive management of the port and the customs left the firefighters to face their death not even bothering to send them the keys to save time and lives. The port’s authorities didn’t even inform the firefighters what was inside the storage that was on fire. This negligence in response from both port authorities hints at a disavowing of responsibility from what was going to be found inside hangar 12.

At the moment an administrative investigation committee has been commissioned to investigate the mismanagement that led to the blast. However, this is going to be a task made for public consumption since the civil administration of the port is under the patronship of the Ministry of Public Works and the Customs administration is under the ministry of finance. The Port Security Authority is under the military intelligence. The Port Security Department is under the general security apparatus. And there is the Information Branch which is under the Internal Security and finally State Security apparatus which is under the ministry of foriegn affairs. Those are the security apparatuses that are in charge of the port security. As for the administrative section it falls under the ministry of transport and public work and the ministry of finance which is in charge of the customs authority at the port. These are the official departments that run the port which means in any investigation all the employees of the various branches mentioned above shouldn’t take part in the investigation committee if it is to be unbiased in its investigation.

Alas, we all know that it will be as the saying goes: hamiha haramiha (protected by those thieving from it) because all the security and executive branches mentioned above are divided according to political favoritism and sectarian quotas. It’s as if we are in the Sopranos where each family gets a share, where each family has loyal soldiers that run their business from within the system. Except that in Lebanon the system was made by colonialism to fit the interest of a few families, the colonial elite of yesterday have today mutated to a club for a handful of families that own the whole country.

Lebanon’s curse is it’s sectarian politics, which means people’s belonging and allegiances are forever directed inwards; as members of a social group, but not as citizens living in a country that has one law or one constitution applicable for all.

The blast blew off the facade of a place that claims to be a country that has elected members of parliament but no assembly that serves its people. It blew off the thin veil off the face of a failed state taken hostage by the banks and oligarchy. The unfolding tragedy that was created by the blast will last and metastasize. It is going to create another tragic turn when all the aid that is now pouring into Lebanon wont find the proper channels or official outlets for the management of equal and efficient distribution. The bags and boxes of donations will sit somewhere in neglect, just like the ammonium that sat in the port until it exploded. Though, unlike the ammonium in such precarious times of scarcity, aid is a crucial necessity that will soon find its way to the market and will be sold instead of it being handed over to people in need as it was intended.

The cycle of history; as if we are used to this chagrin

A hundred years ago 200,000 people starved to death at a time when the population of Mount Lebanon was estimated to be 400,000 people. The Mount Lebanon and Palestine famine caused the highest fatality rate by population during World War I. Historical records revealed a pattern of profiteering and corruption that caused the, preventable, famine.

I remember growing up listening to stories told by my great grandmother recalling how she lived a time in Beirut when corpses were piled on the side of the streets and people resorted to eating cats and dogs. She used to finish her story by telling us in a horrified voice that some of their neighbors resorted to cannibalism.

The explosion on August 4, made more than 300,000 people homeless. Writing this after five days the shockwaves from the blast are still traumatizing the soul and paralysing our consciousness. In two month from now, the cold winter wind will arrive. Lebanon,at the moment, finds itself in the midst of economic collapse, currency devaluation, pandemic, and the loss of the only commercial entry point to the country. Much unity and perseverance is needed in order to prevent the catastrophe from taking on disproportional dimensions.

The most terrifying scenario in my opinion is that the cycle of violence that started by foriegn intervention leading to the civil war that marked my upbringing is now finding its way back through the new circumstances that were created by the blast. Like then, today Lebanese politicians have started to sound the whistle to foriegn saviors to intervene and sort out the post-explosion mess for us. And like back then the same politicians asked the Syrian and israeli militaries to intervene and manage the security of the country. At the moment, some of the same ruling families that sparked the civil war are out on the streets trying to cash in on peoples’ outrage. They have no pride or respect but these are hungry vultures flocking over peoples’ grievings in order to employ it in their next move.

If we don’t act fast, unfortunately, this disaster is going to be exploited and employed politically and it will inevitably lead Lebanon to the next disaster. This is how things function around here in a region that was brutally amputated by colonial designs; that left its local inhabitants to mutate under military occupation, under military dictatorships and warlords. And so after more than 70 years of [in]dependence we reached a time when 2750 tonnes of ammonium sat casually at the port for six years not being perceived as a threat but rather as a possible business opportunity. It’s that kind of disregard to human life; that kind of negligence in Lebanon, that kills people daily.

The port’s explosion has come at a crucial moment in Lebanon. The shockwaves have stripped off the glitzy clout of the City Center symbolising the tragic end of the Lebanese nation state. What remains of it through political rhetoric will become a kind of fetishization of identity and the sauce of warmongering.

Mohamad Ali Nayel

@MoeAliNayel